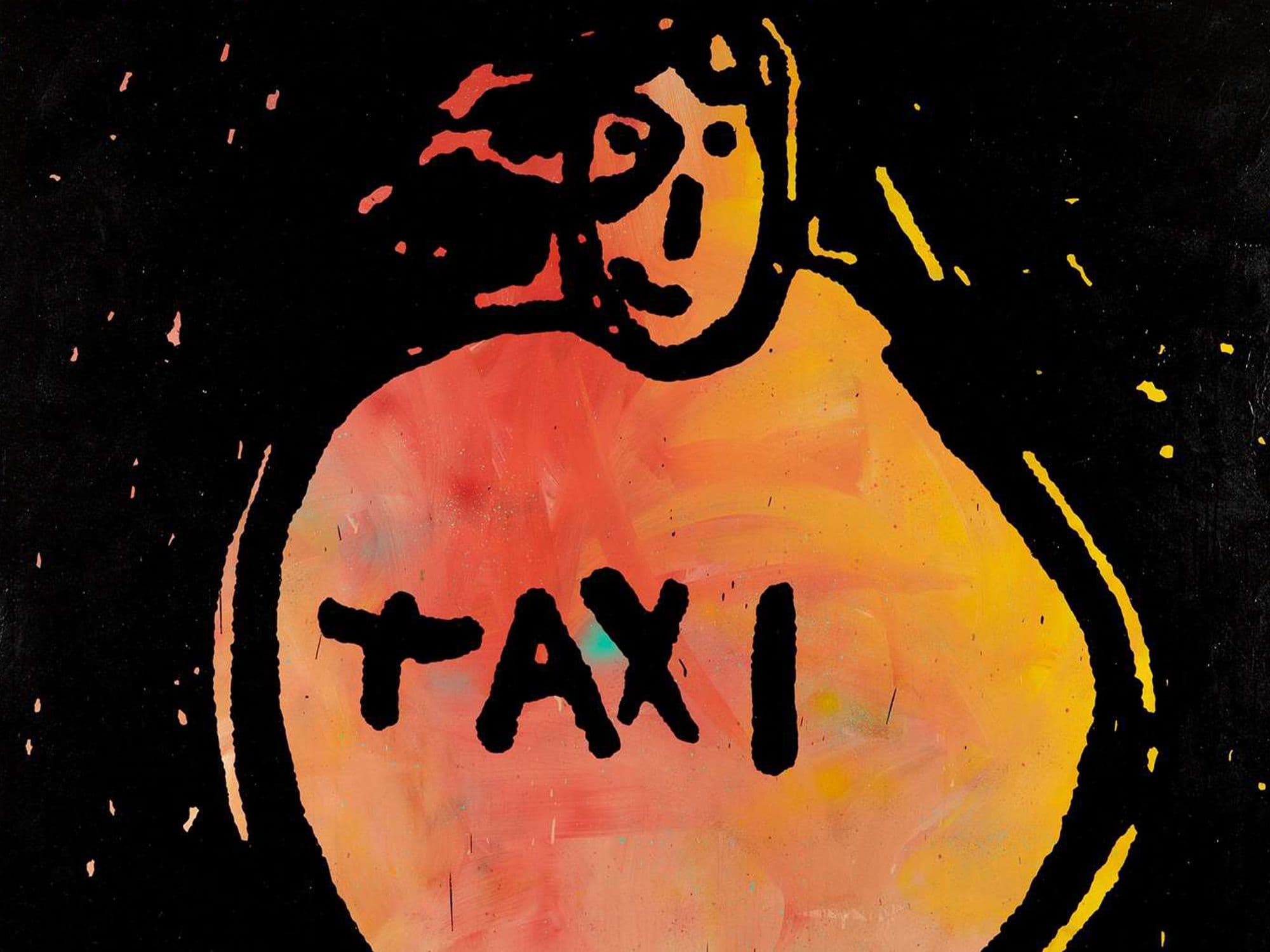

Described by David Pagel in The Times as ‘a master at capturing some of the mystery that lurks just beneath reality’s surface’, Jack Goldstein remains one of the most prominent figures in conceptual art and was heralded for his role in the re-birth of painting in the late twentieth century.

Born in Montreal in 1945, he relocated to California with his family as a child. Goldstein received his training at the Chouinard Art Institute and as a member of the inaugural class of the California Institute of Arts, worked under the celebrated conceptual artist John Baldessari. After initial conceptual performance works in the early 1970s, he became involved in the Pictures Group. Taking their name from their 1977 exhibition Pictures at New York’s Artists Space gallery, the group including well-known figures such as Cindy Sherman and Robert Longo, strove to re-establish the genre of painting, with shared themes such as an interest in representational imagery and references to mass media. During the exhibition, critic Douglas Crimp described Goldstein as the most prominent and most paradigmatic appropriation artist. In direct reaction to this classification, Goldstein decided to start painting, continuing this for the rest of his life to the extent that many remember Goldstein primarily as a painter, rather than for his other achievements as a filmmaker, performance artist, musician and photographer.

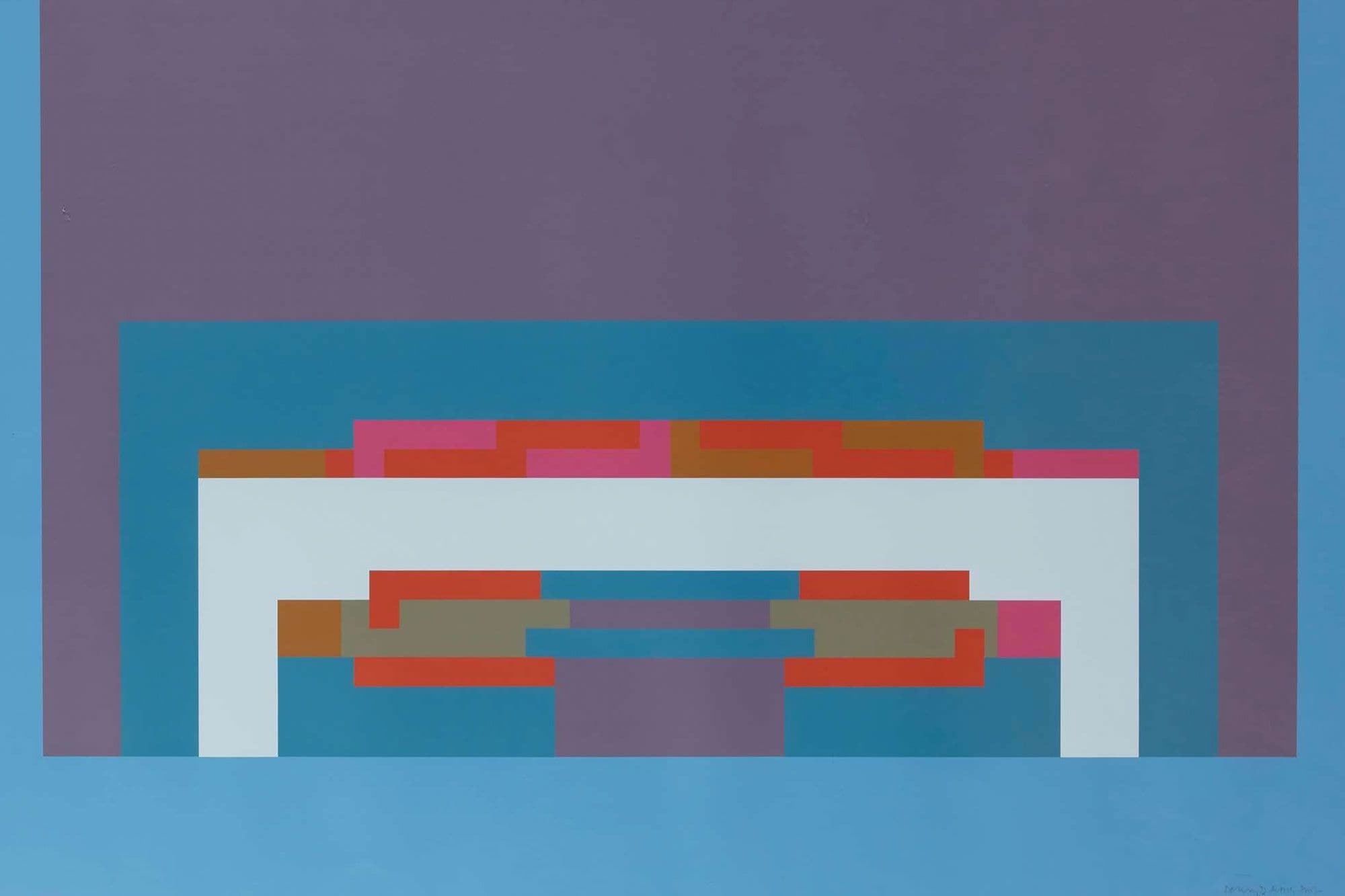

Often struggling with the notions of experience and presence, he was one of the first artists who sought others to carry out the physical production of his work. This desire to remove himself from his practice perhaps echoes his nihilistic explorations of the emptiness and purpose of postmodern society via authorship and documentation.

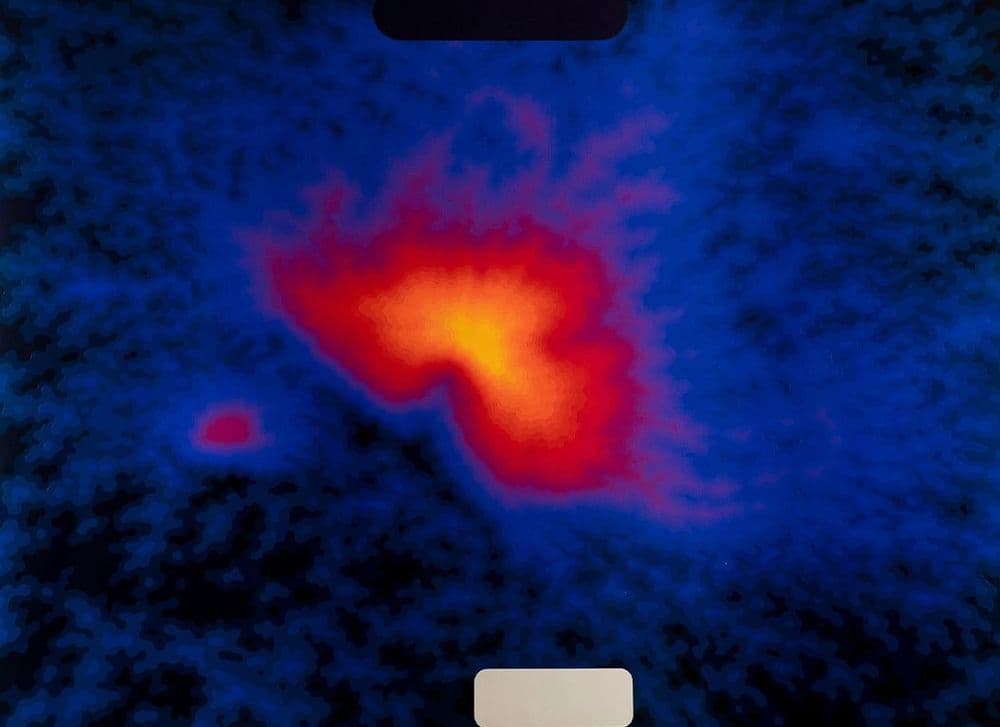

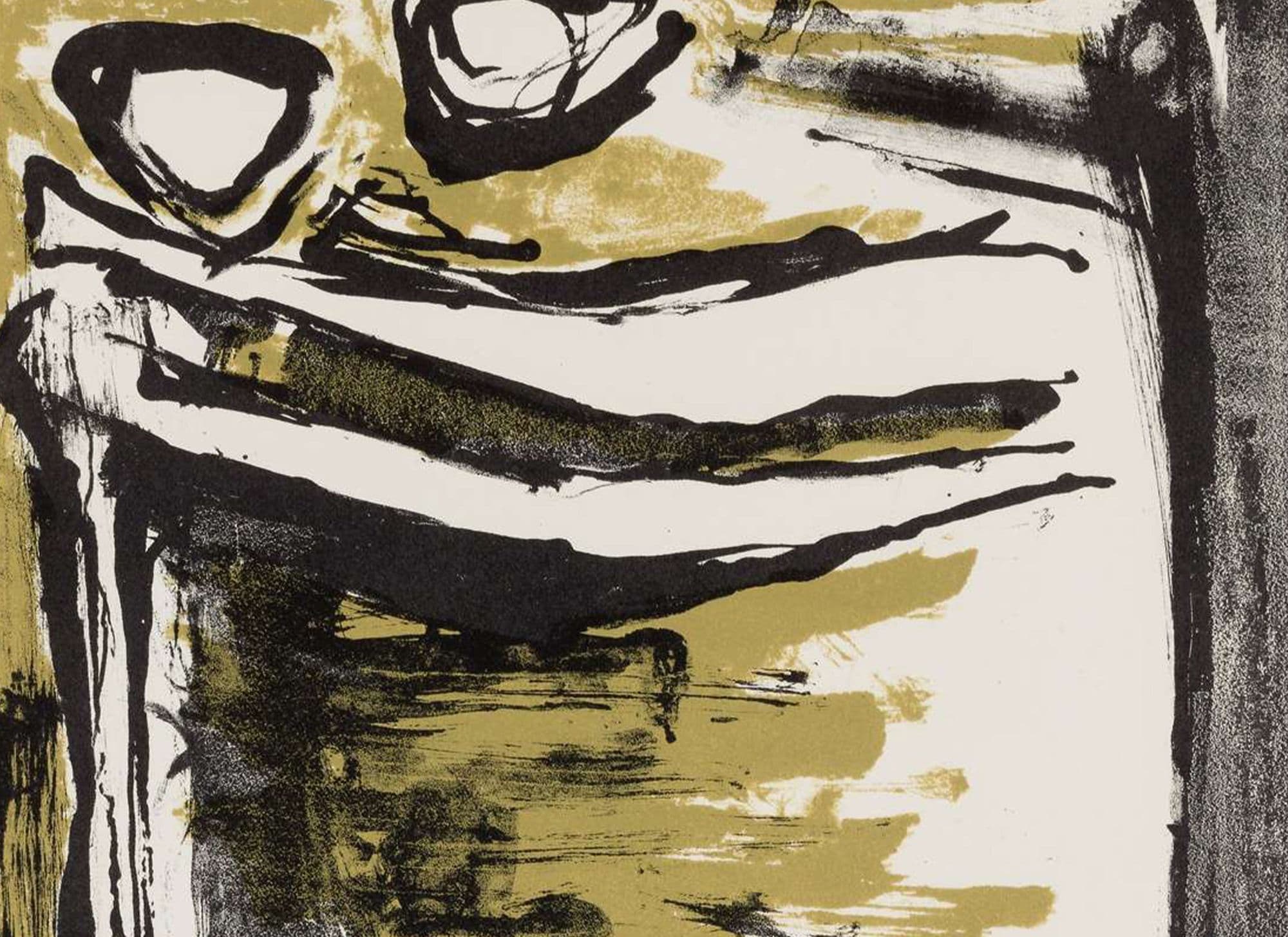

Critic Ronald Jones notably described Goldstein’s painting practice in 1987 explaining...

'Time and again he portrays the spectacular instant, its gorgeous effects: intimidating thunderstorms, majestic views of interstellar space, the staggering effects of computer imaging, the utter silence of night flying. Before his pictures it is natural to remember the vivid and poignant scenes of J.W.M. Turner and Frederic E. Church, or James McNeill Whistler’s Nocturne in Black and Gold: The Falling Rocket. It is natural, but rarely useful. Goldstein portrays the drama of split-second timing, the precipitous vision of the photograph and the video screen. It is his way to leave us without recourse to the narratives so necessary to the meaning of earlier art. Goldstein’s art suspends time and our gaze precisely at the point where origins and endings blur beyond recognition.'

(R. Jones, Jack Goldstein: Recent Work, 1986-1987, New York, 1987, n.p.).