One of the most important Scottish artists of the twentieth century, Alan Davie’s work is instantly recognisable for its spiritual spontaneity and bright eclecticism.

Difficult to pin down, he worked across disciplines throughout his life: as well as exhibiting fine art internationally, he also designed and made jewellery, wrote poetry and performed saxophone, cello and piano music. He insisted that these diverse disciplines should not be approached discretely, instead understanding them to be mutually informative and enriching.

Born to an artistic Grangemouth family 1920, Davie enrolled at the Edinburgh College of Art aged 17 and left with a travelling scholarship. War prevented him from seeking artistic inspiration on the Continent, and the young Davie was instead compelled to enlist. Military duties did not leave much time for painting, so this was a period where he explored the poetic word instead. Following his service Davie returned to Edinburgh and finally headed off on his travels with his new wife, the artist-potter Janet Gaul. They travelled to Italy, where Davie’s eyes were opened by the grace and simplicity of 14th and 15th century Italian art. He was then introduced to Peggy Guggenheim, who took him round her Venetian palazzo and presented to him American Modernism. Davie was particularly struck by the work of Jackson Pollock, who had not yet commenced making his drip paintings but was at the time working in a gestural manner and with a deep affinity with surrealism. Davie returned to London full of inspiration and ready to make art. He had his visual ideas from Italy and an understanding of role of the artist from Paul Klee, “he neither serves nor rules – he transmits.”

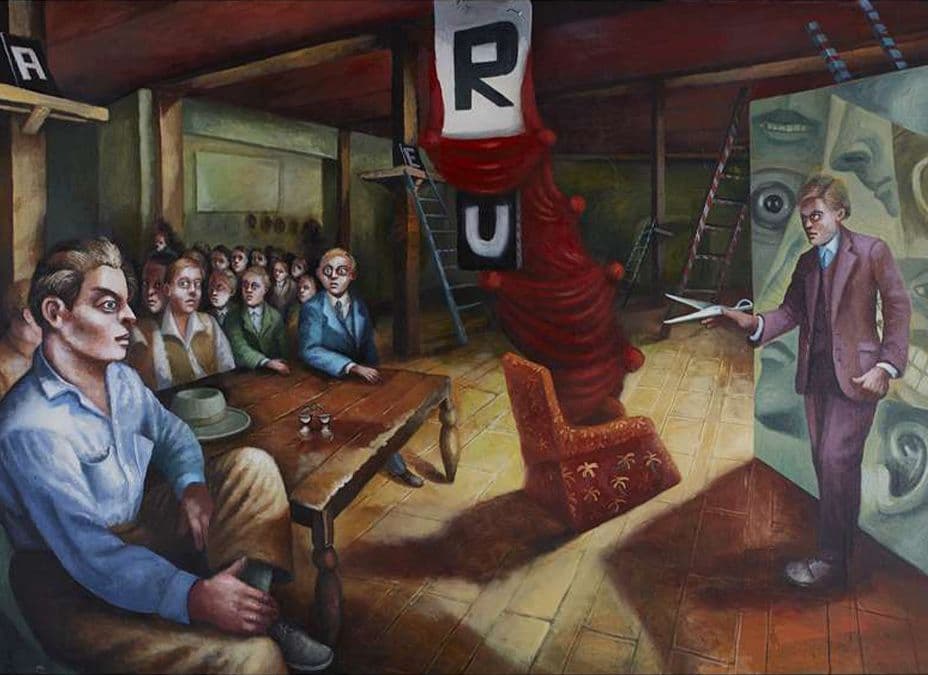

It was at this time that Davie also discovered Zen spirituality and its spontaneity. Davie sought to enact this in his artworks, and he began to engage with his subconscious and to experiment with ‘automatic’ painting in a manner comparable with jazz improvisation. This was the inception of the artistic and creative vision for which Davie’s work is now renowned, but he continued to find inspiration in sources across space and time. He had a specific interest in ancient civilisations and symbols that had recurred across historical cultures. Yet, as Davie’s Guardian obituary so concisely posits, ‘the miracle was that out of an eclectic art that was part Celtic, part tribal Hopi, part Hindu or Jain or Tibetan Buddhist, part African and part pre-Columbian, with a hint of William Blake, there came painting of power and individuality.’ Despite such wide-ranging influences and inspirations, Davie’s art is always unmistakably his.