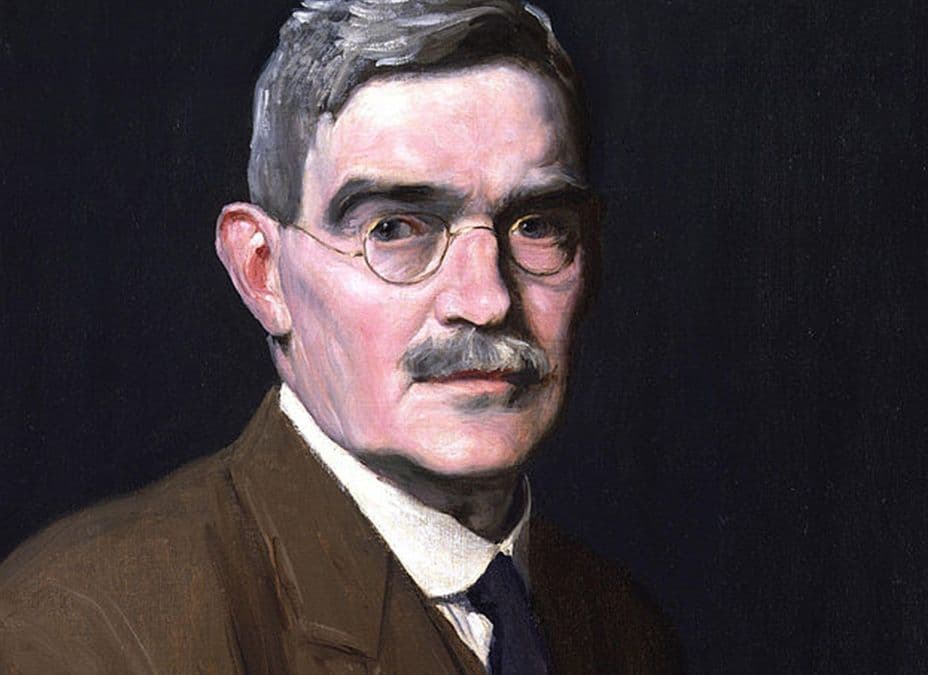

Robert Brough displayed a talent for both art and music from a young age, and was greatly encouraged by the family’s neighbour, the painter Sir George Reid.

With this support Brough found an apprenticeship as a lithographer in Aberdeen and used his earnings to fund trainings at Gray’s School of Art in the city, before applying to the R.S.A. Schools in Edinburgh in 1891.

By the end of his first year, he had been awarded three prestigious prizes, thus beginning a notable career. Brough completed further training in Paris, enrolling at the Acadamie Julien in Paris with Scottish Colourist S.J. Peploe, before travelling on in search of Sisley at Moret-sur-Seine and then Gauguin at Pont Aven in Brittany.

By 1894 he had returned to his native Aberdeen and his steady progress was being closely monitored by the local press, ‘When only three-and-twenty years of age Mr. Brough created some sensation and scored an undoubted triumph with two pictures shown at the Grafton Exhibition of the Society of Portrait Painters. His reputation already extended far beyond the confines of his native land. He had important pictures in Munich, Moscow, and in other leading Continental Galleries’ (1895, Aberdeen Daily Journal).

Then by 1897, and the age of 25, he was in London working on society portraits alongside Sargent. A rising star whose recent paintings had prompted a media frenzy, Brough felt compelled to relocate to the capital to further develop his artistic career. Chelsea was the beating heart of London’s art world; accordingly, Brough took a lease at Rossetti Studios in Flood Street.

Despite his youth, Brough already had the experience and credentials to mark him as an artist of consequence. He had trained in Paris at the Académie Julian, where in 1894 he shared lodgings with Scottish Colourist S. J. Peploe (1871-1935), and following this spent a period working in Brittany, inspired by Paul Gauguin (1848-1903). He was charmed by the traditional way of life of the Breton people, and by the distinctive quality of light and vivid colouring of the landscape.

Both Gauguin and Brough assimilated the tenets of the Synthesist movement, a painting style which prioritised the use of flat planes of harmonious colour and of rhythmic, pattern-inflected composition in favour of naturalistic representation. Brough’s Brittany work firmly acknowledges Syntheticism but is tempered by an observational grounding, owing to his fascination with the Breton peoples’ lives and customs. His paintings from this period constitute a sensitive record of a traditional people, rendered with an innovatively modern, almost post-Impressionist eye.