Born in 1921, Joan Eardley is recognised as one of the great talents of 20th century Scottish art, capturing the energy and community of a quickly disappearing urban way of life in the east end of Glasgow, and the drama and brutality of varying weather effects on the small fishing village of Catterline on the North-East coast. During her lifetime, Eardley was considered a member of the post war British avant-garde who portrayed the realities of life.

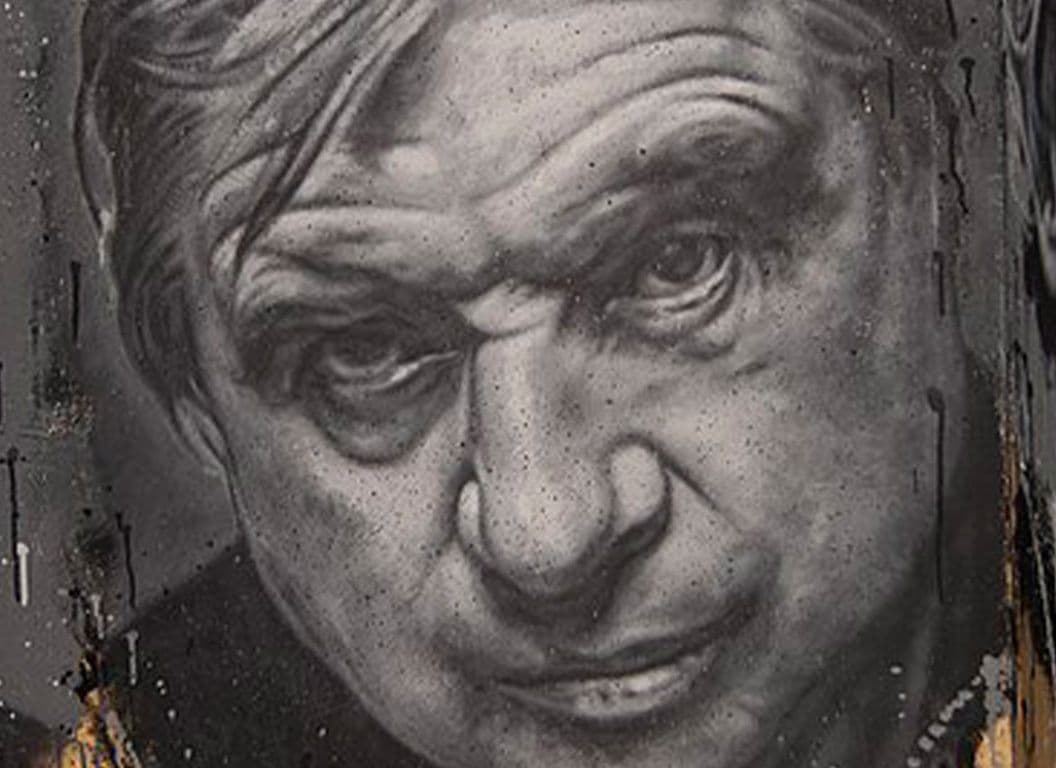

Eardley moved to Glasgow in 1940 and enrolled in the Glasgow School of Art, where she was first allowed the freedom to reject conformity and academic constraints, and to experiment with a new abstraction and expressionism. In her final year, Eardley painted Self Portrait, 1943, which won her the Sir James Guthrie Prize for portraiture. It was during her studies in Glasgow that she discovered the backstreets of the city and became fascinated with the children who innocently and naïvely inhabited them.

Glasgow's Children

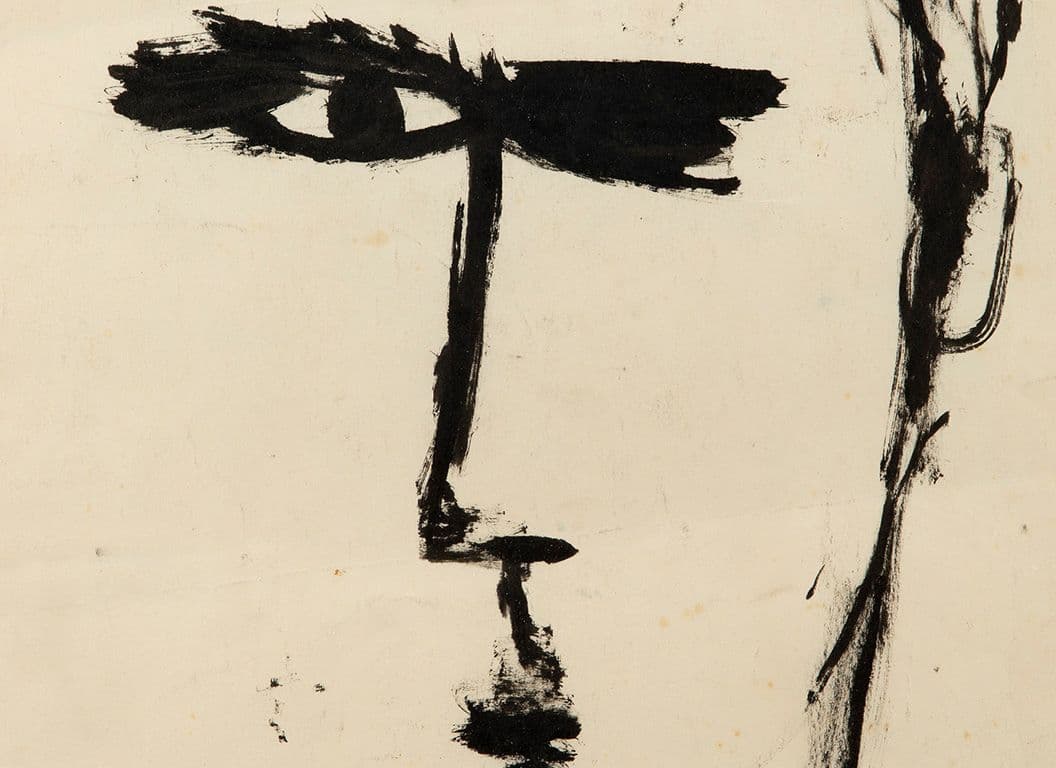

In her Townhead studio, she worked on a series of sketches of the local children, encouraging them to sit for her in exchange for sweets and comics. Devoted to Glasgow, Eardley was particularly drawn to the fast-disappearing areas to the east which were being torn down and re-developed. Nothing represented this more for Eardley than the local children:

“…they are Glasgow – this richness Glasgow has – I hope it will always have – a living thing, an intense quality – you can never know what you are going to do but as long as Glasgow has this I’ll always want to paint.”

She was said to have preferred children as her subjects because they came with ‘no airs and graces, no self-consciousness, and a kind of inward self-absorption’, which she portrayed with a tender but tough reality.

Through combining traditional painting practices with her own unique experiences and interactions with these children and the urban landscape of Glasgow, Eardley’s work serves as a study of a world now lost.