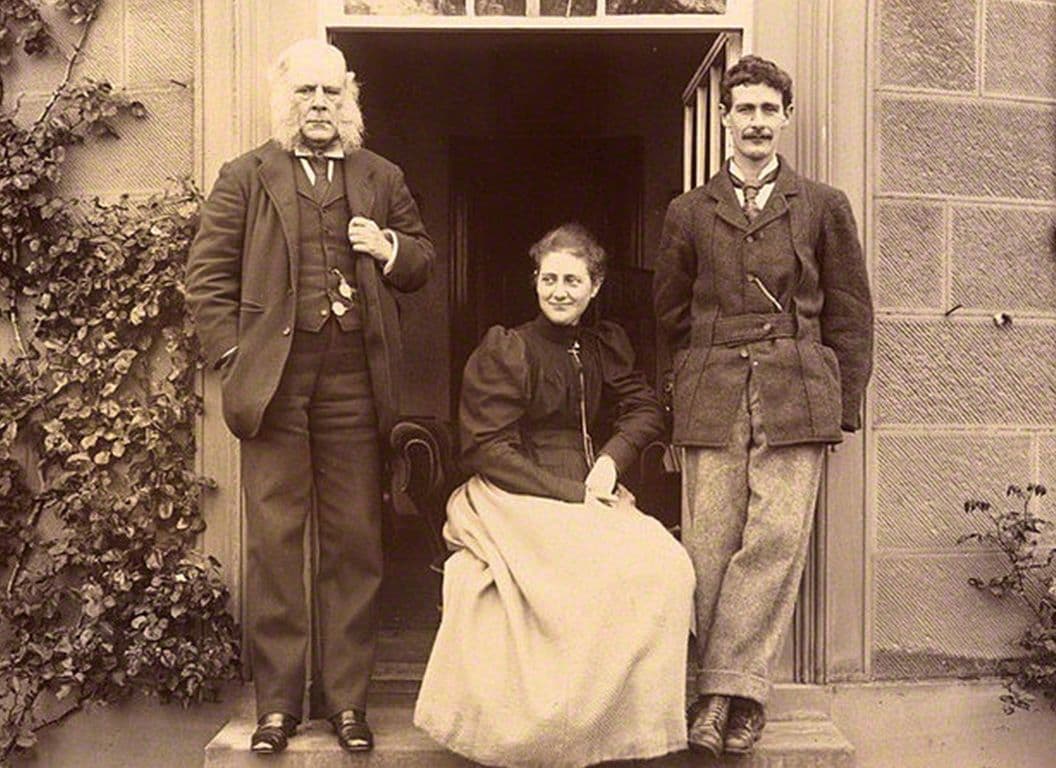

The Introduction of George

In the spring of 1928 Blair moved to Paris to write, in his own words, 'novels and stories no-one would publish'. It was true of his early works that the lines between fact and fiction were often blurred and this made publication problematic for fear of libel action. To earn money he took intermittent work as a private tutor but was often desperately poor and living in the slum conditions where he would meet the various characters who would come to life on the page in Down and Out in Paris and London, his first full length work, published under the pseudonym George Orwell in 1933. By this time, after a few unsuccessful attempts to find his voice, he had developed the plain, direct style that would characterise his work; he believed that writing and ideas should be accessible to people of all class.

After nearly two years in Paris, Blair returned to England where eventually he found a stable teaching post in west-London, but a serious attack of pneumonia put an end to this and he moved to Hampstead where he took up part-time work in a second-hand bookshop. Since 1930, Blair had been reviewing books and writing sketches and poems for John Middleton Murry's Adelphi and he was now moving in literary circles. He would fictionalise this time in Keep the Aspidistra Flying (1936). In 1935 he met Eileen O'Shaughnessy, an English graduate, and they married the following year.

From Wigan Pier to the Spanish Front

Victor Gollancz showed his faith in Blair's talent when he offered him a large advance to write a book about poverty and unemployment in northern England. Spending the early months of 1936 living amongst working people in Wigan, Barnsley and Sheffield, Blair gathered material for what would become The Road to Wigan Pier (1937). Gollancz liked the honest account of coalmining life but was less sure of the highly politicised writing of the book's second half where the author declared himself a socialist but distanced himself from the intellectual wing of the movement that admired and allied itself with Stalin and soviet Russia.

Blair then travelled to Spain to report on the Civil War. Despite his loathing of military values, his even stronger horror of fascism led him to stay on to join the Republican militia. He served on the Aragon and Teruel fronts and it was on the later that he was seriously wounded when a bullet hit his throat. In Homage to Catalonia (1938), written on his return to England, Blair wrote of this time, detailing his experience of trench warfare but also exposing the tyranny of communism and its betrayal of the socialist values in which he believed. He called himself an 'anti-communist revolutionary socialist' and joined the Independent Labour Party.

In 1938 Blair collapsed with a tubercular lesion in one lung and was sent to a sanatorium. During his convalescence he expressed his foreboding of a coming war in Coming Up for Air (1939), a novel which also displayed a keen nostalgia for English traditions and the national character. This and his essays My country, Right or Left and, later, The Lion and the Unicorn, which both make a case for left-wing patriotism, go some way to explain why Blair was so keen to fight when war broke out in 1939. But despite repeated efforts to be accepted for duty he was rejected on grounds of his tuberculosis and instead joined the home guard. In 1941-1943 he became a producer for the Indian service of the BBC, a job he found frustrating because its atmosphere of censorship was so at odds with his fundamental and absolute belief in freedom of speech. "Liberty is telling people what they do not want to hear" he would later say in his essay Why I Write.

During the war Blair, as George Orwell, was writing regularly for Cyril Connolly's influential Horizon, and in 1943 he became the literary editor The Tribune, a left-wing weekly under the direction of Aneurin Bevan. His weekly column, As I Please ranged through a huge number of topics, literary, political and comic, and it set the tone for the lively mixed columns which would soon proliferate in the media. George Orwell was becoming a widely known character, but his compulsive overwork on top of his health problems and the general deprivation of wartime was taking its toll and both he and Eileen were very run down.

Animal Farm and Beyond

Early in 1944 Orwell finished writing Animal Farm, but several leading publishers, including Jonathan Cape, Collins and T.S. Eliot for Faber, turned it down as inopportune while Russia was an ally. It was not published until after the end of the war in Europe, when it would be hailed by critics as the greatest satire in the English language since Swift's Gulliver's Travels, and it brought Orwell a huge international readership; it was translated into every major language. It has survived the collapse of soviet power because its satire can apply to all power hungry regimes, left or right.

Eileen died while Orwell was in Germany reporting on the liberation and opening of the concentration camps. He was deeply shaken by her death but his large literary output continued and he was publishing continuously in newspapers and journals. They had recently adopted a son, Richard, together and Eric was committed to bring him up with the help of a housekeeper. To escape the increasing demands of his literary fame in London and to concentrate on an ambitious new book, Orwell moved to a remote farmhouse on Jura in the Inner Hebrides where conditions were harsh although he had the peace and space that he craved; but he suffered a collapsed lung and was again hospitalised just after the first draught was finished. On his partial recovery, he returned to Jura, typing the second draught of the novel in bed. He would collapse again when it was finished.

The resulting novel, originally titled The Last Man in Europe and published in 1949 by Secker & Warburg as Nineteen Eighty-Four, immediately garnered both high praise and confused criticism. The most complex of Orwell's works, set in an imaginary future, it was the culmination of his thoughts and ideas; but in its portrayal of the fears and dilemmas facing humanity, it offered little by way of solution. There was much critical debate as to its message and meaning. Although undoubtedly in part a response to its author's long reflection on the tyrannies of Nazism and Stalinism, it was also a warning against the less obvious but no less pernicious forces of manipulation and coercion through mass media, and the banality of its methods, "rubbishy newspapers containing almost nothing but sport, crime and astrology". It is also about the danger of censorship, something Orwell experienced at the BBC. Much of this still resonates with readers today and has remained hugely popular, selling especially well in times of war and political upheaval. In fact, his greatest fame and readership have been posthumous. He coined many terms which remain in popular usage, notably, the 'Cold War' and from Nineteen Eighty-Four, 'Big Brother', 'thoughtcrime' and 'newspeak.'

"What I have most wanted to do is to make political writing into an art" Orwell wrote in his essay Why I Write in 1946. By the time of his death from a tubercular hemorrhage in January 1950, he had achieved this aim.

Three months before his death, Orwell married Sonia Brownell, formerly Cyril Connolly's assistant on Horizon. Although unsuccessful in her attempt to nurse him back to health, she provided comfort and humour at the end of his life. His political affiliations were sometimes complicated but he remained a democratic socialist until his death. Although an atheist and highly critical of the Christian faith, Orwell maintained a deep love of the traditions and liturgies of the Anglican Church, choosing to be buried in All Saints' parish churchyard, Sutton Courtenay, Oxfordshire. It was a final irony in the complex life of a private and simple man.