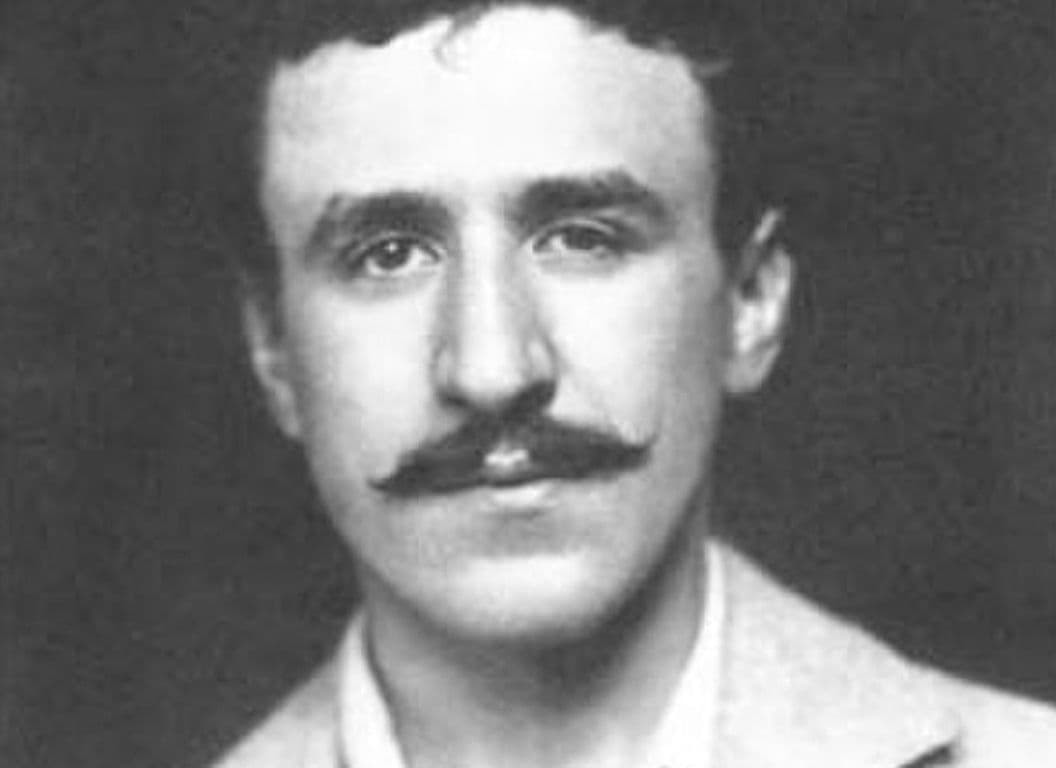

Born in Glasgow in 1834, Christopher Dresser was the son of a tax collector and in his career he became Britain’s first professional, independent, industrial designer.

After enrolling at the Government School of Design in London, at the age of thirteen, Dresser was exposed to the ideas of leading design reformers such as Richard Redgrave, Henry Cole and Owen Jones.

The Design Philosophy of Christopher Dresser

His early designs were informed by his study of botany; a relatively new scientific discipline, yet the innate knowledge he developed on the subject earned him a doctorate in absentia from the University of Jena. In 1860 he was elected a Fellow of the Edinburgh Botanical Society. However, his work his work was transformed by his trip to Japan in 1876 as the official representative of the Victoria & Albert Museum, and the first European designer to do so after Japan opened to the West in 1854.

Dresser’s basic principles of design centred around Truth, Beauty and Power, and unlike William Morris, his direct contemporary, Dresser fully embraced new production techniques in colour, pattern, material and ornamentation. Throughout his career Dresser worked with innumerable manufacturers to produce objects which were well designed and available to the masses.

Linthorpe Art Pottery

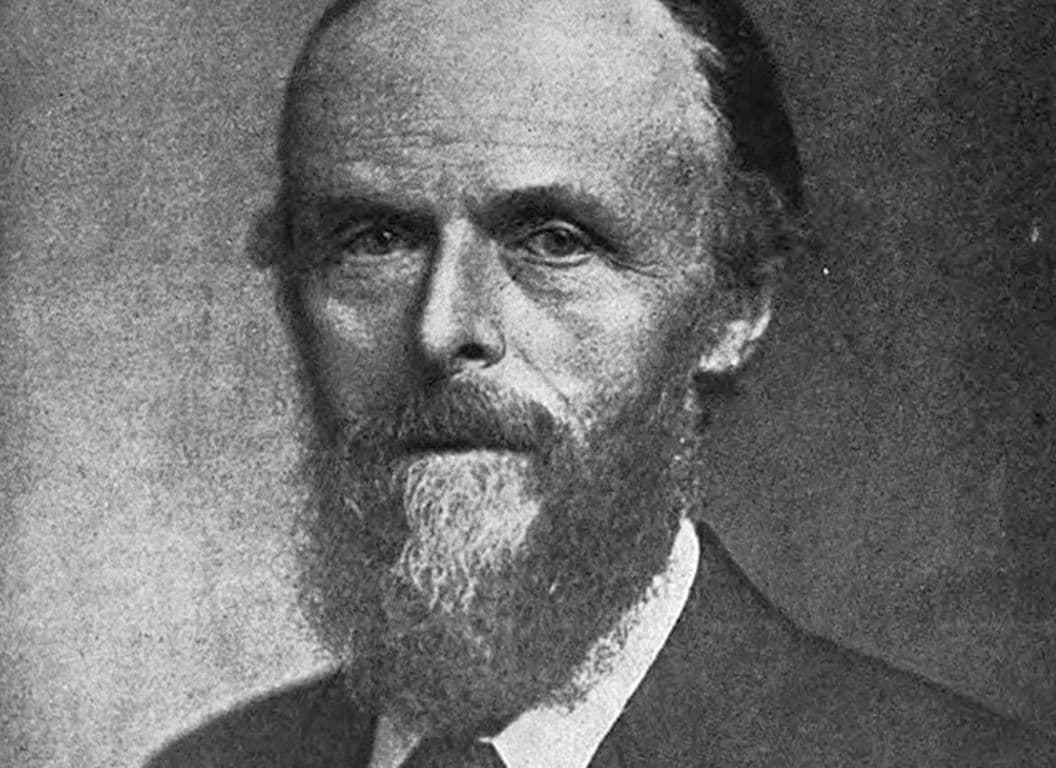

In 1879 Dresser co-founded Linthorpe Art Pottery in Middlesborough with local entrepreneur John Harrison. Keen to remedy the high levels of deprivation and unemployment, the two set out to create a prosperous working environment with a highly trained workforce and fair pay regardless of gender. In the years that followed the firm employed over 100 people, including skilled workers from the Staffordshire Potteries and artists trained at the Schools of Art, South Kensington. Dresser persuaded master potter Henry Tooth to oversee the production of wares and for three years Dresser himself was ‘Art Superintendent’ of the firm.

Designs for Linthorpe were broadly informed by his visit to Japan, however it is clear he drew from many other sources including Roman glass and Peruvian and Fujian pottery, which he studied in the British Museum. The striking wares at Linthorpe represent Dresser’s belief that the even the most common of materials can be transformed into things of beauty. Rich glazes & sculptural qualities revealed his skill in creating interesting and exciting shapes.

According to Dresser, an object which perfectly fulfilled its function was beautiful in itself and needed no ornament and this view is perhaps best realised in his designs for metalwork for firms like James Dixon & Sons and Hukin & Heath. Around this time, Dresser was at the height of his powers: his designs for these indicate his thorough understanding of materials, form and function.

Dresser’s bold but ill-fated retail project, The Art Furnishers Alliance, was established in 1880 on New Bond Street in London. Dresser retailed the goods he designed as well as importing Japanese art, employing two of his sons as the company’s agents in Japan. However the business was not to last: growing financial problems and Dresser’s progressively poor health led to the company’s demise in 1883.

Later Life & Death

Towards the end of his life Dresser turned his attention to wallpaper and textile designs. Sadly, his daughters were not able to maintain his design studio after his death in 1904, however his posthumous reputation as a proto-modernist and mark him out as one of the greatest talents of 19th century design.

Many who cover their walls with costly paintings have scarcely an object in their houses besides these which has any art merit…Surely persons whose houses are thus furnished have bit little real love of the beautiful; he who admires what is pleasant in form and lovely in colour would regard the beauty of each object around him and the tout ensemble.