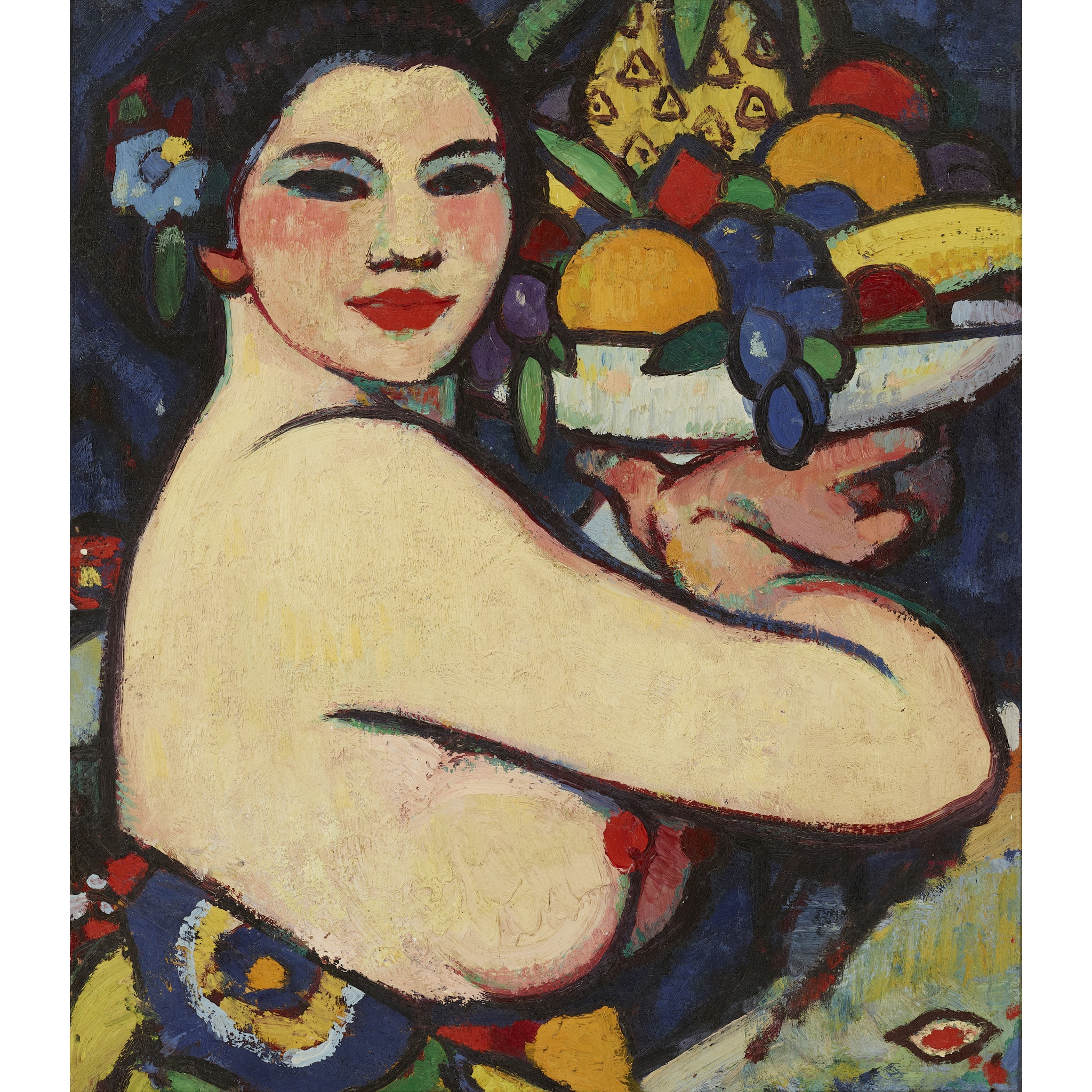

ANNE ESTELLE RICE (AMERICAN 1877-1959)

A BOWL OF FRUIT

£112,700

Scottish Paintings & Sculpture

Auction: Evening Sale | Lots 103-196 | Thursday 05 December from 6pm

Description

Signed with the artist's eye ideogram and inscribed on the reverse 'Anne Estelle Rice Paris '11', oil on board

Dimensions

61.5cm x 53cm (24.25in x 20.75in)

Provenance

Given by the Artist to G. Holbrook Jackson in 1911;

Given to Mrs. Margerie Carnegie;

Christie’s, London, 6 November, 1981;

Fine Art Society Ltd., November 1981;

Bourne Fine Art, Edinburgh;

Private Collection, Scotland.

Exhibited:

Baillie Gallery, London, 1911

Literature:

Carol A. Nathanson, The Expressive Fauvism of Anne Estelle Rice, Hollis Taggart Galleries, New York, 1997, repr. b/w. p.22, fig.24

Footnote

Anne Estelle Rice grew up in in the industrial Schuylkill Valley in Pennsylvania, the daughter of a ‘Scotch-Irish’ father and a Pennsylvania Dutch mother. After training as a graphic artist, painter, designer and muralist in Philadelphia, she began work as an illustrator – one of the few professions that offered the prospect of financial independence for women of her generation. Drawings published in the likes of Collier’s and Harper’s Bazar [sic], and as covers for the venerable Saturday Evening Post, led to a commission to go to Paris in 1905 to illustrate the latest fashions and scenes of Parisian life for the North American.

Within three years, Rice had surfaced in the mainstream of French modernism, exhibiting six paintings at the 1908 Salon d’Automne. Elected a Sociétaire of the Salon two years later, she also served as a juror in 1912. Her radical, monumental Egyptian Dancers, inspired by the Ballet Russes, and one of the five murals commissioned for the Wanamaker department store in Philadelphia in 1909 were both accorded place d’honneur in Salon hangs. The artist’s work was also shown at other salons and galleries in Paris, and in London, Cologne, Brussels and Budapest.

Her meeting with the Scottish artist John Duncan Fergusson at Étaples in 1907 had proved critical to both and probably prompted Fergusson’s decision to move to Paris, where Rice became muse and model for many of his most celebrated paintings. Their six-year relationship evolved from one of mentor and protegé into an equal and mutually beneficial partnership. They appear to have experimented with new styles, primarily Fauvism and Cubism, and adopted new subject-matter at around the same time, their approaches becoming increasingly divergent.

A Bowl of Fruit was painted in 1911, when both were exploring what could be described as the romantic nude, figures emblematic of the élan vital at the heart of Henri Bergson’s philosophy. For Rice in particular, fruit and flowers were symbols of sensual pleasure as well as fecundity, and cornucopias such as this feature in Egyptian Dancers of 1910 and several of her illustrations for Rhythm magazine. While this figure’s intensely red lips and nipples recall Fergusson’s nudes, the directness of her gaze does not. A preliminary drawing indicates musculature omitted in the painting (Tate Archive). Here, smooth, golden skin and strong, sinuous contours enhance the figure’s soft sensuality. Her bold Fauve palette and stylized, circular forms rhythmically repeated create a decorative surface as well as suggesting plenitude. Rice’s debt to Paul Gauguin is apparent in the mood and subject-matter of this image of a strong-bodied Polynesian. It is also revealed in the lush colour orchestrations involving rose, orange, pink and violet that transform the figure’s flesh into another kind of luscious fruit. The Salon d’Automne had staged a Gauguin retrospective in 1906, inspiring a new generation of artists to return to the primitive and naïve, and to the spiritual.

A symbolic reading of this composition is encouraged by the presence of Rice’s eye signature, an ideogram adopted around this time and which features on the catalogue cover of her 1911 show at the Baillie Gallery in London. This device may owe something to Gauguin’s sunflower ‘eyes’, the Egyptian eye of Horus or to the Eastern mysticism that interested the Rhythm circle. The introduction to the Baillie catalogue was written by the British critic and essayist Holbrook Jackson, re-used from an earlier appreciation published in the journal Black & White (Holbrook Jackson, ‘Personal Expression in Paint: The Work of Estelle Rice’, Black & White, 11 March 1911). Rice’s ‘work scintillates with a new vision of light-filled colour’, he wrote, concluding on its right, ‘on the obvious grounds of sincerity of craft and distinction of vision, to a front-rank position in modern art.’ By way of thanks, Rice offered him a painting of his choice. He chose A Bowl of Fruit.

We are grateful to Susan Moore, author of a forthcoming monograph about Anne Estelle Rice, for writing this catalogue note.