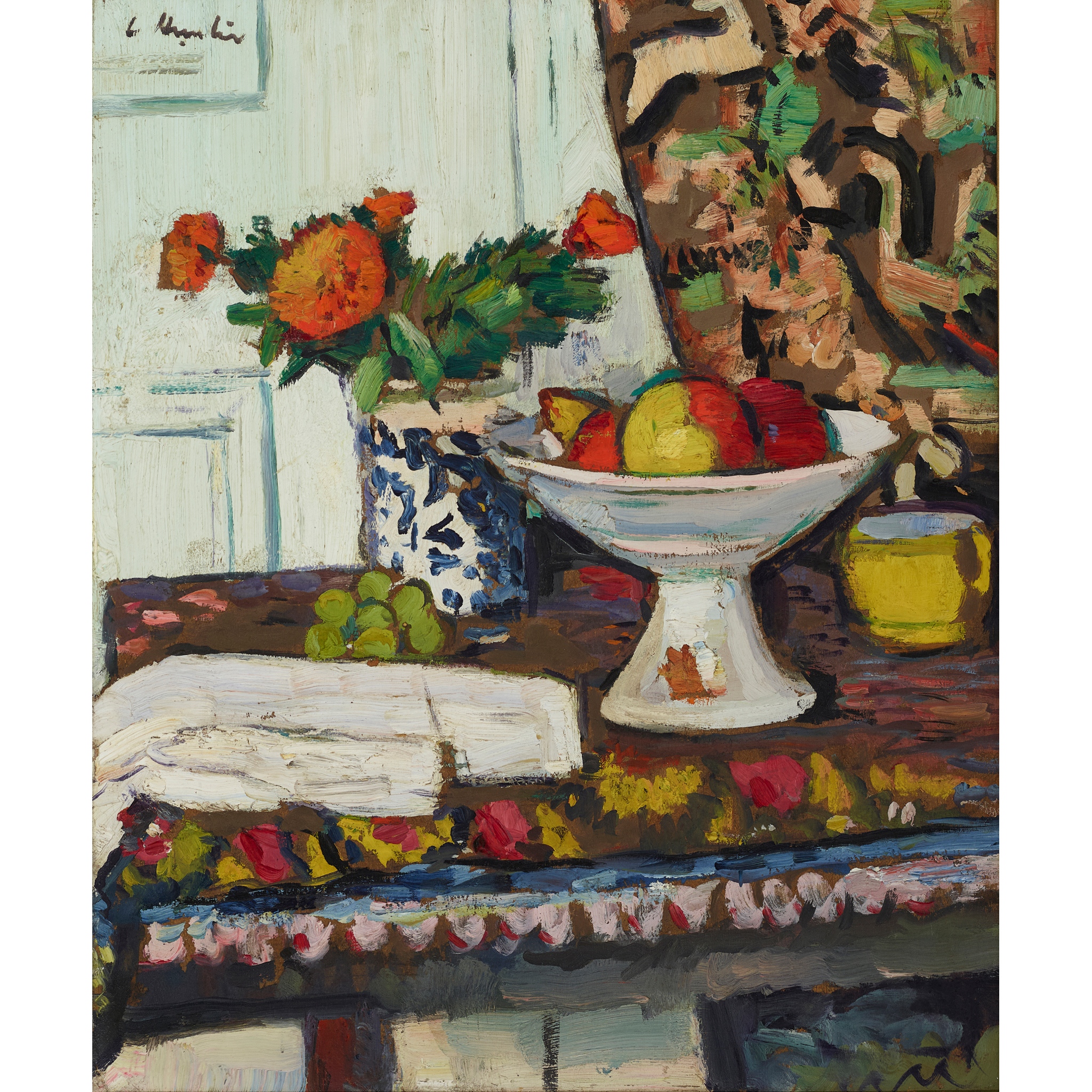

Lot 166

GEORGE LESLIE HUNTER (SCOTTISH 1877-1931)

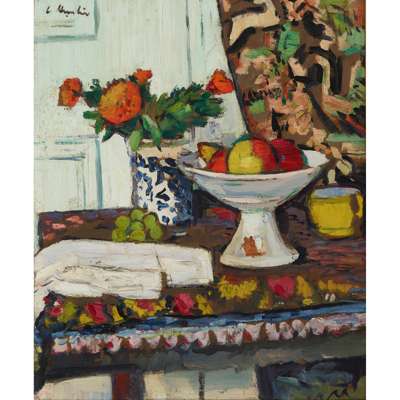

MARIGOLDS WITH THE YELLOW CUP

Scottish Paintings & Sculpture

Auction: Evening Sale: Lots 100 to 191 | 06 June 2024 at 6pm

Description

Signed, oil on board

Dimensions

61cm x 51cm (24in x 20in)

Provenance

T. & R. Annan & Sons Ltd, Glasgow

Footnote

Marigolds with the Yellow Cup is the sister picture to the painting Peonies in a Chinese Vase in the Fleming Collection, London (acc.no.(FWAF/RF144). Their work has been exhibited under the title 'Still Life with Fruit and Marigolds in a Chinese Vase' and was chosen as the cover image for Bill Smith and Jill Marriner’s monograph Hunter Revisited: The Life and Art of Leslie Hunter (Atelier Books, Edinburgh, 2012). Their description of the Flemings painting can equally be applied to Marigolds with the Yellow Cup, namely:

“Hunter’s mastery of colour and texture reveals a new sensuous quality. While perspective is flattened, it is not to the severe extent of Matisse’s oversimplification. His liberated sense of pattern comes together, striking colour chords that vibrate across the surface. Hunter’s inspired brushwork ensures the richness of colour glows with energy. Clive Bell, the noted English art critic, was greatly impressed when he viewed the painting in an exhibition at Reid and Lefevre’s London gallery in the 1930s of work by contemporary British artists - some well-known, some less so – and commented ‘That is the finest picture in this exhibition. I do not know who painted it.’” (see Smith and Marriner, op.cit., pp.125-126)

Marigolds with the Yellow Cup is a leading example of Hunter’s still life paintings of the 1920s, when he was at the peak of his career. He brings together still life objects of contrasting form, nature by way of fruit and flowers, pattern – especially in the tablecloth and Persian curtain hanging on the wall to the right - colour throughout, asymmetrical balance and painterly bravado.

As Smith and Marriner have pointed out:

“Hunter had reached a point whereby colour, form and harmony were instinctively assured, allowing him to experiment with a variety of features as integral parts of a stronger design. Of course not all this change can be attributed to Matisse. Indeed the root of this transformation lies more fully in Hunter’s extensive knowledge of Cézanne’s oeuvre. The late still life paintings of Cézanne frequently include a floral-patterned curtain that drops behind a table, acting as a distinctive colour field with which other distinctly-coloured areas of the composition can interact…The combined effect of the form and grouping of the central still life elements has a wonderful sculptural quality, while the colours almost vibrate with energy. This new emphasis is borne out by his stated intention in early 1923 to devote himself to line and form.” (Smith and Marriner, ibid., p.110)